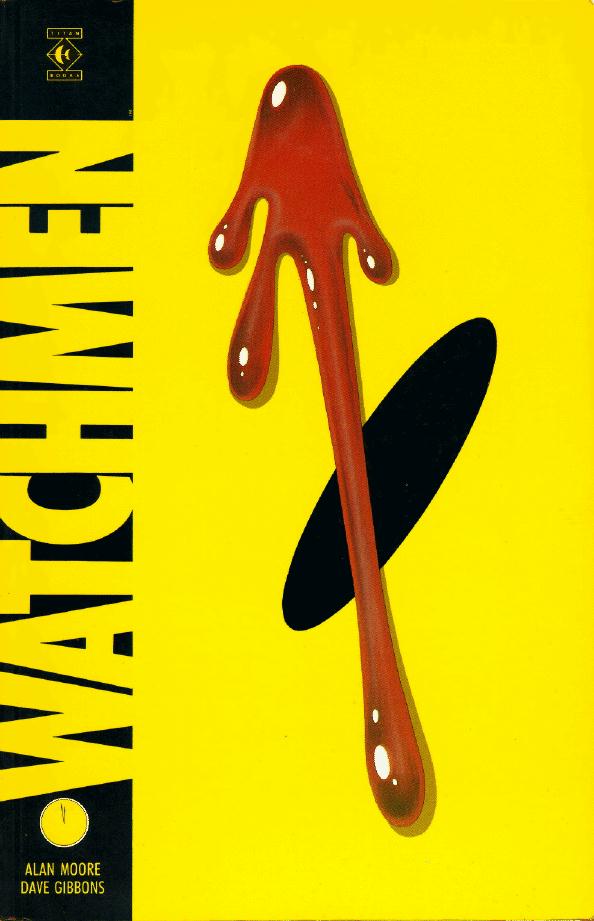

I figure, if I’m going to start writing new trade reviews for the site, where else to start than with the granddaddy of them all? There’s nothing I can really say about Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen that hasn’t already been said repeatedly throughout the time since the first issue appeared on comic stands in September 1986. It was the only graphic novel to crack Time Magazine’s list of the “All-time 100 Greatest Novels”. Its been described as a “watershed in the evolution of comics” by Time, and “the greatest super-hero story ever written” by Entertainment Weekly.

I figure, if I’m going to start writing new trade reviews for the site, where else to start than with the granddaddy of them all? There’s nothing I can really say about Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen that hasn’t already been said repeatedly throughout the time since the first issue appeared on comic stands in September 1986. It was the only graphic novel to crack Time Magazine’s list of the “All-time 100 Greatest Novels”. Its been described as a “watershed in the evolution of comics” by Time, and “the greatest super-hero story ever written” by Entertainment Weekly.

But just in cast you haven’t read any of that stuff, here’s my take on Watchmen. To call the book a revolution in the medium of graphic storytelling, or even a new way of looking at how to create a comic book, would both be underselling its significance. Both creators and readers are still catching up to Watchmen. It is, as in the words of Dave Gibbons, “a comic about comics”, just as Citizen Kane is a film about films – not in that the subject matter of the work is about its respective medium, but that in both cases, the telling of the story is always secondary to dissection of, and experimentation with, the very medium they were utilizing. The book has layers upon layers of symbolism, subtext, and repeated iconography that not only cannot be discovered by the readers in their initial reading of the book – people are still finding new strokes of brilliance within the book. This is, in large part, why each reader’s experience with the book is always subtly different. Unlike most writers, Moore never tells you what to feel, or what conclusions to draw based on what happened in the story. He simply reports the facts to you, and gives you all the tools you need to come to your own answers of who was right, who was wrong, and what it all means in the end.

The book is comprised of 12 chapters, each of which is equivalent to one of the 12 issues which made up the series. In the graphic novel, these issues are presented in the exact form as when they were originally released, as the series was released without ad support, and the covers each served as the first panel of the story within. These covers were only the start of how Watchmen defied contemporary (both then and now) wisdom in comics by challenging the forms and structures that had for so long defined the medium. Each page within the book was a variant of a simple nine-panel grid. Long have comic illustrators struggled with the issue of panel-layouts, because they focus the reader’s attention, and, if applied properly, propel the reader along the author’s intended path at a brisk pace. But somehow, perhaps only through sheer force of will and detailed visual trickery, Watchmen manages to keep such a simple layout consistent throughout 338 pages of graphic fiction, and yet still propel the reader with an ease and pace consistent with the most innovative layouts imaginable. This same layout structure allowed for the book to toy with the readers perceptions in a number of places, creating strange senses of deja vu, despite the story moving consistently forward in the fifth chapter, fearful symmetry, which is entirely symmetrical in its structure, and exactly asymmetrical in the subjects of the panels. On page 10, we have an oversized panel with Dan on the left in the foreground, and Laurie on the right in the background – while on page 19, the adjoining page if you follow the books symmetry, we have the same panel, only Dan is on the left in the background and Laurie is on the right in the foreground. On pages 4-5 and 24-25, you have scenes featuring Rorschach and Jacobi, only in the former, all the scenes highlight Jacobi’s fear, while keeping Rorschach in the shadows, while the latter highlights Rorschach’s fear, while keeping Jacobi in the shadows.

The book similarly plays with colors and point-of-view, switching repeatedly between hot-and-cold colors dominating a scene to create a sense of unease and urgency, and in fight scenes, giving us the point of view of both the attacker and the attacked. Which brings me to another point – obviously, Watchmen was a milestone by which the “maturification” of comics is often measured, with its pitch-dark story, un-shy approach to nudity and sex, and often uncomfortable levels of violence. The difference, though, between Watchmen and all the various books that came after it is that Moore shows us the consequences of all these actions. How different does a batman story become when you see it through The Joker’s eyes? When you feel every punch as once again the bones in your face begin to snap as blood flows freely from seemingly every pore and you pass out from the pain? But Batman stories (as much as I love them) are seldom concerned with the aftermath of the violence, instead moving on to the next exciting event to hold the reader’s interest. Not so with Watchmen. Each act of violence man commits against his fellow man in this book is examined in close detail, showing the effects on the bodies of attacker and attacked, their minds, and the bodies and minds of those affected by the violence, both present and not. It is worth noting, though, that despite the inherent bleakness of the book and its outlook on the human condition, it begins with a horrific act of violence (the famous murder of the Comedian), but ends with an ironic message of hope.

I guess now I can finally get around to saying a few words about the story and characters of the book, although, as I mentioned previously, they’re far from the most important part of it. The plot is set in an alternate-reality version of the 1980s, where the US won the Vietnam War through the intervention of super-heroes, Nixon is still in office, and the Cold War is on the verge of becoming feverishly hot. Against this backdrop, The Comedian, a costumed-adventurer-turned-government-agent, is murdered. Thrown out of a window many stories above the point where there would be even the slightest hope of survival. Rorschach, the only hero still operating after the 1977 Keene Act forced his kind into either Government service or retirement, investigates the murder with an eye towards a “mask-killer”, and brings the news to his former comrades. This sets in motion a long and convoluted chain of events culminating in a catostrophe that makes the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 look like a mere trial run. Along the way, people and super-people are drawn together, torn apart, shifted around, and made to feel more realistically than anyone you’ve seen on HBO or AMC. For a man who’s been a recluse most of his life, Alan Moore understands the human condition better than anyone I’ve ever known.

A final word – Its unlikely that anyone reading this will be unaware of the 2009 film by Zack Snyder which was based on Watchmen. If you’ve seen the movie, but not yet read the book, please, for your own sake – don’t judge the book by its film adaptation. As is the case with many adapted stories designed for a certain artistic medium, Watchmen was simply not a story that could be translated faithfully, because the work as it was originally intended is not just a comic book, it is of comic books. Its a celebration of everything the medium has been, the growth it’s shown, the prejudice it’s endured, and most importantly of all, even 25 years later, where it’s going.

And let me tell you, the road looks pretty golden from where I’m standing.